News

better business decisions

Posted 3 years ago | 8 minute read

How vulnerable are gas supplies?

Recently there has been an ongoing discussion about energy security. This has been caused by tensions affecting international relations, and the emergence of new geopolitical threats. As one of the main sources of primary energy, natural gas is an obvious subject of interest in this discussion. But how reliant are the UK and Ireland on imported gas and oil, and if supplies are disrupted what are the risks?

Gas supplies in the UK and Ireland

Natural gas plays an important role in the energy mix, accounting for around 30% of UK energy production in 2020, and 40% of demand. UK gas demand decreased 6% in 2020 compared to 2019, following several years of stable demand and was largely a result of restrictions in place to curb the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the UK the largest single source of gas supply continues to be the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) with approximately 48% of total supply in 2020. UK gas production has been broadly stable for close to a decade following several years of decline since the peak in 2000, but the UK remains a major producer of natural gas, sitting within the top 20 gas producing countries globally and the third largest in Europe. But the maturity of the UKCS means supplemental supplies are required from international markets. In 2020, indigenous production met more than half of demand with the remainder supplied via imports.

For the UK the highest imports of gas are from direct pipelines across the North Sea from Norway, which is the second-largest external supplier to the European market after Russia. Pipeline imports from Norway are sourced via the Langeled pipeline, which makes landfall at Easington (England) and the Vesterled and FLAGS pipelines, which make landfall at St Fergus (Scotland). These imports account for around a third of total supply (over 266GWh in 2020). This compares with direct imports of LNG from Russia at just 25GWh in 2020.

Ireland currently has two main sources of gas supply – the Corrib gas field and imports from the UK via two gas interconnector pipelines. According to Gas Networks Ireland’s latest Winter Outlook report, the Corrib gas field is expected to meet approximately 21% of gas demand in 2021-22, having reached a production plateau in early 2018, with the remaining 79% being imported from the UK via a pipeline at Moffat in Scotland.

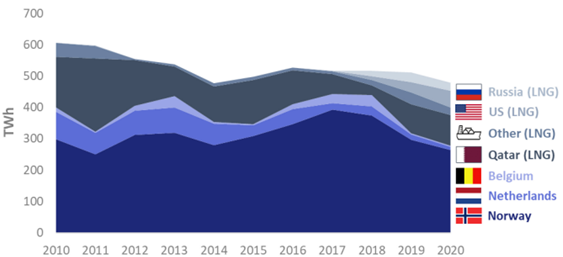

UK imports of gas, 2010-20

Source: BEIS

UK, Ireland and European interconnections

While on the surface the relatively small proportion of direct imports of Russian gas to the UK and therefore Ireland, seem like supplies should be secure. But the interconnected gas market means this comparison isn’t quite as simple as it seems and there remains a risk for supplies given the proportion of UK gas imports coming through Europe. The UK is physically connected to the continental European market by two interconnector pipelines under the English Channel: The Interconnector from Bacton (UK) to Zeebrugge (Belgium), and the Bacton-Balgzand Link (BBL) from Bacton (UK) to Balgzand (Netherlands).

The limitation on UK imports of Norwegian gas is not pipeline infrastructure, but Norwegian production and the fact that a significant proportion of that production is exported to France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany via five pipelines (Franpipe, Zeepipe, Norpipe, Europipe I, and Europipe II). With Norwegian production at maximum capacity, the UK could only receive more pipeline gas from Norway if some of those volumes were diverted away from continental Europe.

A connected market

The UK has no direct pipeline connection to Russia, and imports of LNG from Russia accounted for just 4% of total UK gas supply in 2021. However, any disruption in Russian pipeline gas deliveries to the European market would almost inevitably cause prices on European trading hubs to surge. This surge would affect the dynamics of pipeline movements both between the UK and Norway and between the UK and continental Europe, while simultaneously influencing the dynamic of LNG imports into Europe.

In 2021, imports provided 87% of the gas supply to Europe (the EU plus UK), while EU production provided 13% of supply. This means Europe is heavily import-dependent.

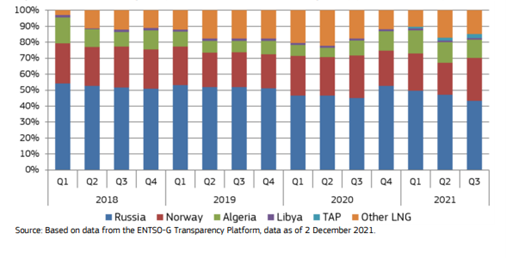

According to the latest data from Europa, the share of gas imports from Russia (pipeline and LNG together) amounted to 43% in Q3 2021 (the lowest since Q1 2015, but still the highest share by exporting country), split by 41% of pipeline imports and 2% of LNG. The share of Norway (the second largest exporter to the EU) was 27% in Q3 2021 and the share of Algeria was 11.5%

Share of EU gas imports*

Source: Europa

*includes both pipeline and LNG imports

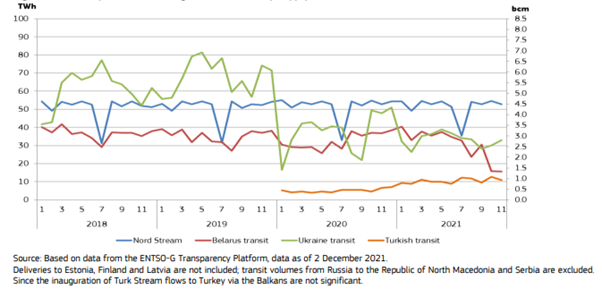

There are four main routes for Russian pipeline gas into Europe – Nord Stream 1 via the Baltic Sea to Germany, the Yamal-Europe pipeline to Germany via Belarus and Poland, the various Ukraine routes to Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Poland, and the pipelines to Turkey (Blue Stream and Turk Stream), with onward connections to Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary. In addition, there are pipelines for direct deliveries to the Baltic states and Finland.

EU imports of gas from Russia by supply route

Source: Europa

What could the impacts be?

In the last few months of 2021, a combination of factors pushed wholesale gas prices up to severe and long-lasting highs. The result was that energy bills across the world rose. But in the UK, the system designed to keep prices as low as possible for domestic consumers presented a problem. Once spot prices for gas rose beyond the retail price cap, operating costs for utilities soared as prices rose and energy use increased into colder months. Any disruption to Russian pipeline gas supplies to Europe would almost certainly bring further volatility in gas prices.

If a disruption to Russian gas supplies were to occur, especially before the end of the present winter, the result would be price spikes across Europe. The UK would face price spikes similar to those in other European markets, despite the UK not being directly dependent on Russian pipeline gas supplies. A sharp increase in wholesale UK gas prices – beyond the already high level seen at present – would have dramatic implications for multiple sectors

The first impact would be that prices on European hubs would rise more rapidly than those on the UK gas market (NBP). This could lead to gas being bought on the NBP, and then exported to continental Europe to be re-sold on European hubs at higher prices. If UK gas demand remained constant, this would tighten the UK market and cause prices to rise.

At the same time, producers of gas at offshore fields in Norway that sell their gas into the spot market, and have the option between selling to the UK and selling to continental Europe across one of the five pipelines connecting Norway with European markets, could shift volumes to those markets if prices remain at a premium to those on the UK NBP.

With gas inventories already lower than normal and the fuel continuing to play a key role in power generation (particularly to balance out variable renewable power generation), for heat, and in heavy industry, these developments will have a critical influence on energy markets in the short to medium term. A price spike could result in energy intensive industries rationing production or halting operations. During the price peaks last autumn for example when CF Fertilisers paused production as gas prices made its operations uneconomic – a move which had knock on impacts to wider supply chains. But due to a current lack of alternatives, gas consumers would be forced to continue using gas despite high prices.

What about Nord Steam?

As countries look to impose sanctions of Russian businesses, it was reported on 22 February that German chancellor Olaf Scholz has ordered the country’s economy ministry to ensure the certification process for the pipeline remains on hold after escalation of the tensions between Russia and Ukraine.

Bundesnetzagentur, which regulates Germany’s electricity, gas, telecommunications, post and railway sectors, suspended the certification process in November last year. The process cannot continue until Germany has reassessed its supply security, which “will certainly take some time,” said Scholz. Economy and climate minister Robert Habeck said the “one-sidedness of dependence on one supplier, who has also proven to be unreliable, must be overcome”.

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which is physically complete, would take gas from Russia to Germany. The pipeline, which would have increased European reliance on energy from Russia, has been a major source of contention in Europe and the United States. It cost €10bn (£8.4bn) and was completed in September 2021. Nord Stream 2 runs parallel to an existing gas pipeline, Nord Stream, which has been working since 2011. Together, these two pipelines could deliver 110bn cubic metres of gas to Europe every year. That is over a quarter of all the gas that European Union countries use annually.