News

better business decisions

Posted 2 years ago | 4 minute read

Four takeaways from the IPCC’s 2021 climate science report

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has published its first update on the physical science of climate change since 2013. Here we round up four key messages from the report.

- We are set to pass 1.5C warming by 2040

Under all emissions scenarios outlined, the earth’s surface warming is projected to reach 1.5C or 1.6C in the next two decades. That leaves a very narrow pathway to stabilising temperatures at 1.5C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century, the most ambitious target of the Paris Agreement. The immediate, rapid, and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, that would limit warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C is believed to be beyond reach now.

- Human activity is driving extreme weather

The report shows that emissions of greenhouse gases from human activities are responsible for approximately 1.1°C of warming since the beginning of the century. There is “high confidence” that human activities are the main drivers of more frequent or intense heatwaves, glaciers melting, ocean warming, and acidification. “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean, and land,” the report concludes.

- We know more about regional climate impacts

Climate models have improved enabling scientists to understand what the impact of global climate change will look like in different parts of the world. Over the coming decades, climate changes will increase in all regions. For 1.5°C of global warming, there will be increasing heat waves, longer warm seasons, and shorter cold seasons. At 2°C of global warming, heat extremes would more often reach critical tolerance thresholds for agriculture and health.

- We are closer to irreversible tipping points

The report sounds the alarm about the possibility of irreversible changes to the climate., “The probability of low-likelihood, high impact outcomes increase with higher global warming levels,” the report notes. “Abrupt responses and tipping points of the climate system, such as strongly increased Antarctic ice sheet melt and forest dieback, cannot be ruled out.”

Michael Phelan, CEO and Co-founder of GridBeyond, commented:

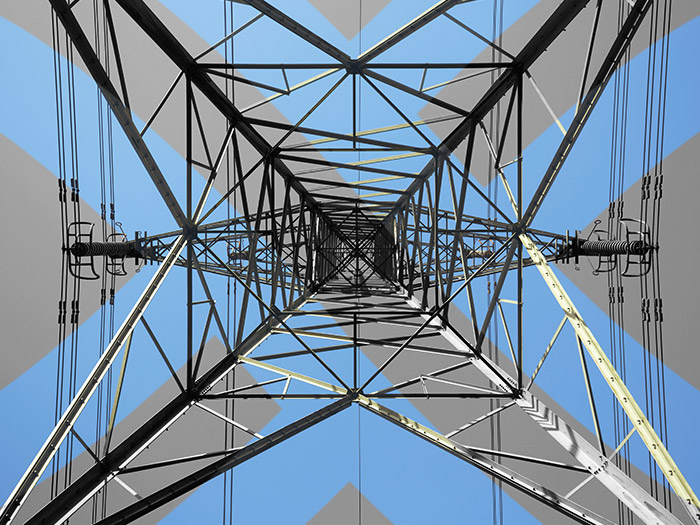

“Severe weather is a major cause of disruption to electricity supply. Over recent years the dangers of extreme weather conditions and their impacts on electricity have been most recently demonstrated in the USA with Texas experiencing a severe cold weather in February, and northern states facing problems from heatwave this summer. In the UK, winter 2013-14 saw particularly cold storms which resulted in 750,000 households across the UK being affected by power disruptions.

“Predicted increases in temperature, precipitation, sea levels and storm surges are expected to increase the severity and frequency of natural hazard threats to critical energy infrastructure, including exposure to flooding, extreme temperatures, and subsidence. This may increase the risk of interruption to the electricity supply.

“Stabilising the climate will require strong, rapid, and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Some of the solutions and technologies to advance decarbonisation and to tackle the climate emergency are already here. They exist and have proven to be effective, affordable, and reliable. Full decarbonisation of our economy needs to start with eliminating fossil fuels from our energy system, and that is only possible when the grid implements digitalisation to the point it can accept greater levels of renewable and decentralised generation and unlock greater flexibility.”

The IPCC’s assessment reports come in groups of three. This first one, published today, outlines the projected impacts of five emissions scenarios, which range from global net negative and net zero to emissions doubling by 2050 and 2100, compared to current levels. The second and third reports, due to be published next year, will look at how to adapt to these impacts.