News

better business decisions

Posted 8 months ago | 6 minute read

Government must cut business energy costs: Jobs Foundation

In the first in a series of research papers examining the core factors driving job creation and growth across the UK, charity the Job Foundation highlights the impact high energy prices are having on Britain’s industrial base.

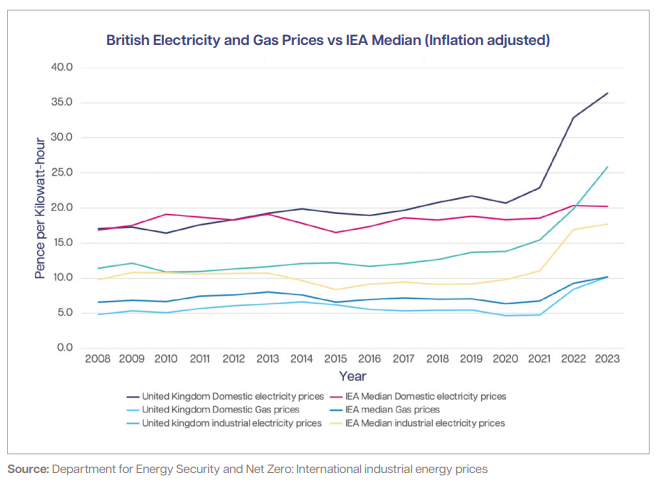

The report, published alongside the government’s Industrial Strategy, maps the areas in the UK most reliant on energy-intensive industries and analyses the sectors most impacted by high energy costs. Nothing that UK industrial electricity prices are among the highest in the developed world, with British firms paying on average 46% more than companies in comparator countries. For large industrial users, this gap rises to over 100%. The result is a severe cost disadvantage in global markets. As a result energy-intensive industries are shrinking or closing altogether. Between 2021 and 2024, chemical output fell by 40%, and British steel production has collapsed from 12 million tonnes in 2013 to just 4 million in 2024. Aluminium, paper, glass and fertiliser plants have also closed or scaled back. It also noted that high energy prices are a direct barrier to growth in emerging sectors, including data centres, AI infrastructure and advanced manufacturing. Public policy has worsened the problem, with a complex web of levies and market mechanisms, such as the Climate Change Levy, Contracts for Difference, and the Capacity Market, driving up prices.

The UK chemical industry, valued at £13B in gross value added (GVA) and £28B in turnover (rising to £30B GVA and £45B turnover when including pharmaceuticals), is one of Britain’s largest manufacturing sectors. It directly employs around 62,000 people, with the Chemical Industry Association estimating it supports as many as 500,000 jobs across the broader economy.

Clustered in industrial regions such as Teesside, Humberside, Merseyside, and Grangemouth—with additional presence in Southampton—the sector is highly reliant on both natural gas and electricity. The energy intensity of chemical production, when measured against GVA, is 17%, a figure that significantly exceeds broader industrial averages. Since 2020, a series of closures underline the sector’s vulnerability. Major employers have also scaled back production of ammonia and fertilisers, citing unmanageable energy costs.

The report stresses the urgency of energy cost relief and strategic investment to prevent the offshoring. It suggests targeted government support to upgrade and protect regional chemical clusters and retain domestic capabilities in commodity and speciality chemicals.

British steel production has dropped from 12M tonnes in 2013 to just 4M in 2024, and employment has declined precipitously. Once a global leader, the UK now ranks 26th in global steel output. The sector’s energy intensity, when assessed against GVA, is 79%, the highest of any industry examined in the report. Steelmaking is particularly sensitive to electricity costs, especially with the shift from blast furnaces to electric arc furnaces (EAFs), which are 75% electricity-dependent.

The report calls for a £3B UK Green Steel fund to support electrification and the transition to lower-carbon production methods.

The UK’s glass industry generated £4B in turnover and £1B in GVA in 2022, supporting over 20,000 direct jobs. The energy input for glassmaking makes the industry highly vulnerable to electricity costs. As a result, even large firms face competitive disadvantage against foreign producers with access to cheaper energy.

British Glass, the industry’s trade body, has developed a 2050 decarbonisation roadmap. The report recommends that government align investment and energy policy to this roadmap, ensuring long-term viability. This includes reducing policy-driven levies, offering capital support for clean heat technologies, and making long-term energy contracts more affordable.

Cement manufacturing, has declined from 11M tonnes in 2001 to 7.6M tonnes in 2023, even as imports surged. The sector has a relatively high energy intensity (12% of GVA), making it extremely susceptible to both fossil fuel costs and carbon levies. The capital cost of full decarbonisation is estimated at 470% of the industry’s annual turnover, which the report said is unfeasible without external support.

The cement industry, according to the report, requires targeted subsidies or carbon pricing reforms to incentivise clean energy transitions. It advocates for capital investment in carbon capture technologies, support for kiln upgrades, and long-term protection against volatile gas prices to prevent the collapse of these strategic, geographically dispersed industries.

With a turnover of £23B and a GVA of £8.3 billion, the plastics industry is a major employer and exporter. British capacity stands at nearly 2 million tonnes of primary plastic production annually, but imports still account for around half of domestic consumption. Energy-intensive polymer synthesis from petrochemicals like ethylene and propylene underpins this sector’s vulnerability.

The report underscores the need to re-shore more of the plastic supply chain by stabilising energy prices and supporting lower-carbon production processes. Policy incentives for circular manufacturing and investment in green polymer research are highlighted as tools for future resilience.

Aluminium production has seen dramatic contraction. From a capacity of over 300,000 tonnes in 2009, the UK now operates a single smelter. The process is highly energy intensive, around 14,000KWh/tonne, so is sensitive to energy price spikes.

To avoid total offshoring, the report calls for more robust shielding from energy levies, support for long-term contracts with renewable energy providers, and regional industrial zoning with preferential electricity rates.

The biomass-linked sectors (paper, pulp, and wood) employ thousands, and are highly mechanised and energy-dependent, but vulnerable due to narrow profit margins.

The report recommends continued levy exemptions and investment in energy recovery and combined heat-and-power (CHP) infrastructure to reduce the cost burden and improve energy efficiency.

Although not traditionally industrial, data centres are energy-intensive infrastructure critical to emerging sectors like AI, fintech, and supercomputing. The report highlights that electricity costs for UK data centres reach up to £0.52/KWh, compared to £0.08 in Iceland.

The report urges policymakers to classify data centres as strategic infrastructure, establish low-cost energy zones, and incentivise domestic server hosting. Without these steps, the UK risks falling behind in AI capability and cloud computing services.

How GridBeyond can help…Introducing Process Optimizer

Process Optimizer acts as your operational co-pilot, enabling precise energy management and intelligent load control across energy markets. Helping you cut costs, access new revenue and meet net zero goals, all without sacrificing product output or quality.

By leveraging accurate forecasts up to 7 days ahead, real-time data analysis, advanced machine learning algorithms, and seamless integration into existing plant infrastructure, Process Optimizer uses digital twin technology to forecast maximum value strategies and ensure process stability.

It then delivers market-aware optimisation and AI-powered process control: dynamically aligns and adjusts on-site assets to avoid price peaks and unlock hidden value in demand-side response, arbitrage, and energy trading, while ensuring product integrity.

View the demo

Intelligent demand side response- White Paper

In today’s fast-paced industrial landscape, optimising production schedules isn’t just about meeting deadlines; it’s also about navigating volatile energy prices. Fluctuations in energy costs can significantly impact operational expenses, making it imperative for businesses to devise strategies that mitigate against these costs.

Learn more